Reanimating and Reconsidering ‘Othello’

13th February 2023

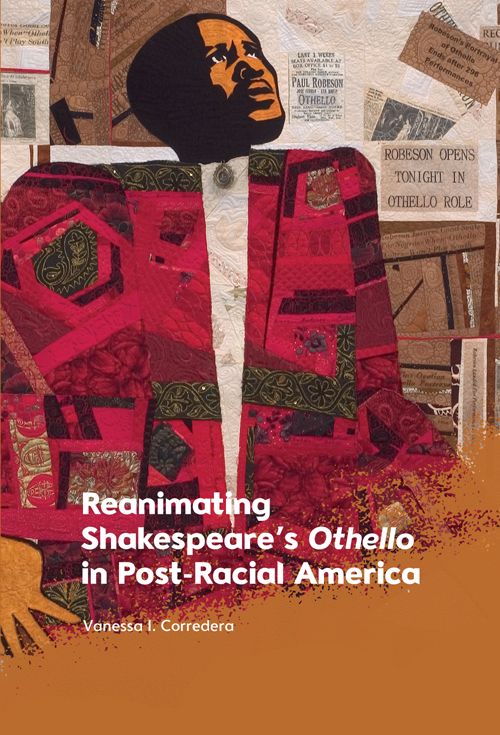

Vanessa I. Corredera (Associate Professor at Andrews University) writes about her work on Othello in ‘post-racial’ America and her recently published monograph, which is available from Edinburgh University Press.

Given my scholarship on what in my book I call “reanimations” of Shakespeare’s Othello—essentially, works that either briefly or more extensively engage with and therefore bring Othello back to life in the modern era—academic friends frequently ask whether I have heard about/seen/read the latest reiteration of Shakespeare’s (in)famous tragedy. Such was the case recently when someone posted in the Shakespeare Society Facebook group about Frantic Assembly’s adaptation of Othello at the Lyric Hammersmith. I had not heard of this adaption, so I followed the Facebook link to learn more. While I know that one should rarely, if ever, look at online comments, I could not help myself, and I was struck by two observations. First, several commenters noted that they had taken their students to see this adaptation of Othello. Second, the longstanding debate about whether Othello is a racist play or a play critiquing racism reappeared in the comments. In my book, Reanimating Shakespeare’s Othello in Post-Racial America (Edinburgh University Press), I trace how the racial frameworks (the strategies for conceptualizing race) so popular in America’s supposed “post-racial” era (2008-2016) frequently result, even if unintentionally, in anti-Black versions of Othello. To instead craft an anti-racist engagement with Othello, I reveal, takes significant, intentional care both with the racial frames used to interpret Othello and with the details that comprise the work, whether a performance of the play, a comic book rendition of the titular character, or a comedy sketch referencing both. I therefore wondered: What racial frameworks did Frantic Assembly use when adapting Othello? How did those frameworks shape their artistic decisions? And were the students who saw the adaptation properly prepared to assess whether it perpetuates racist caricatures or critiques racist systems, whether, in other words, it is an anti-Black or anti-racist Othello?

Though Reanimating Shakespeare’s Othello focuses on reanimations of Othello in America and in an era that can in hindsight seems especially naïve, the principles I explore in the book for considering race and/in Othello can nevertheless help scholars, creators, and teachers engage more ethically with the play. While the belief in a post-racial society has receded, the racial frameworks of the post-racial era I discuss in the book linger. And though scholars consider these frameworks most often in relation to the U.S., the stereotyping and therefore scapegoating of minoritized identities for racial inequity instead of attending to systemic issues, the appeal to the so-called “colourblind” view of race, and the continued privileging of white perspectives are employed far beyond America’s shores. I thus offer key questions that all who engage with Othello—from scholars to adaptors to theatermakers to teachers to the everyday audience member—can ask in order to assess more effectively the racework undertaken every time this by-and-large “toxic” play is brought back to life.[1]

1. Does this reanimation of Othello take a colour evasive approach?

First, a word on the term colourblind, which was long used to convey the ideas at the heart of what is now called colour evasive. People rightly note that it is an ableist term and that we should therefore avoid employing it. Though I do so in my book, I want to rectify that usage here. While no one term has yet to replace colourblind when it comes to discussions of racial perspective and/or casting, I think the proposition of colour evasive is an especially thoughtful and effective substitution.[2] In discussions of post-racial America, however, philosophers, political theorists, sociologists, and performance studies scholars all employ colourblind to describe the fundamental approach toward race underpinning the post-racial era: “not seeing” race. Essentially, to be what we would now call colour evasive entails considering each race as if society treats them equally, as if racial inequity no longer exists. Often, people conceptualize not recognizing race as the more polite, even ideal attitude, as if the concept of race is the issue and acknowledging race the problem. The true issue, however, occurs when people ignore racial inequality, and with it, racism. But what does this mean for Othello?

Too often, creators who re-animate Othello do not truly pay attention to race, approaching the play as if a tragedy where a Black man marries and murders a young white woman can ever be race-neutral. The reanimations of Othello I study, however, suggest that when creators are inattentive to race, their versions of Othello frequently depend on stereotyping, racial caricatures, and one-dimensional versions of the titular character, thereby making them anti-Black. Yet short of creators saying they do not focus on race, which they usually do not say expressly, how can we tell if they are taking this approach? One place to start is by paying attention to the ways they frame their reanimation.

For instance, in my Introduction, I demonstrate how when creators argue that the play is not about race and/or gesture toward their emphasis on so-called “universal” themes such as jealousy, it often means they are not thoughtfully considering race in Othello. Additionally, the care any work takes toward confronting race in Othello may be perceived by analyzing promotional materials. As I argue in Chapter 1, how we visualize Othello matters and gives insights into the racial perspectives taken when reimagining the character. For instance, in the promotional poster for Frantic Assembly’s Othello, why does only Desdemona meet the viewer’s gaze? What should we make of the fact that Othello’s shirt is positioned half-way up his back, exposing his body to the viewer? What racial dynamics does this tableau tap into or contest? If one discerns that care has not been taken concerning race and representation when promoting a particular reanimation, one can in turn be wary about a similar lack of care in the work itself.

2. Does the reanimation meaningfully push back against the stereotypes of Black masculinity triggered by Othello?

The violent Black man. The rage-filled brute. The Black Buck. These are all common stereotypes about Black masculinity that reanimations of Othello can easily invoke, even if unintentionally. After all, audiences see Othello’s rage as he confronts Desdemona’s supposed infidelity, and that rage eventually becomes murderous. While Othello may not rape her, the intimate nature of the strangling on their nuptial sheets nevertheless evokes the threat that Black masculinity supposedly poses to white femininity as envisioned in the stereotype of the Black Buck. Yes, some of these racial caricatures may have American histories. But as American cultural artifacts such as police procedurals with Black men as gangsters or hip-hop songs comprised of stanzas glorifying violence and demeaning women circulate globally, so too do these distortions of Black men. Thus, audiences within and outside of the U.S. may likely bring these stereotypes to bear upon reanimations of Othello.

It is therefore vital for creators who reanimate Othello across mediums to craft a complex vision of Black masculinity, such as the one developed by Keith Hamilton Cobb in the play American Moor (Chapter 4). Through the central figure of the unnamed actor auditioning for the role of Othello, Cobb depicts a Black man justifiably angry at the systems that delimit and oppress him, but a man who is also funny, earnest, loving, and creative. He may be virile, but he is no threat, adamant, but never violent. And importantly, through this actor, Cobb also articulates a multifaceted vision of Othello in stark contrast with the white director’s facile one. Depictions like Cobb’s vitally counter versions of Othello reduced to mere caricature, such as what I argue can be found in the comic series Kill Shakespeare (Chapter 1), where Othello is nothing more than a brutish, violent soldier reduced to a status so abject that he comes across as less than fully human. To craft an anti-racist Othello therefore means developing a nuanced, multidimensional, and decidedly non-stereotypical Othello. Anything less is unequivocally anti-Black.

3. Does the reanimation inculcate sympathy for both Desdemona and Othello?

In Chapter 5 of Reanimating Shakespeare’s Othello, I address what I call the “Desdemona problem,” namely, the difficulty creators and audiences alike have when it comes to feeling sympathy for Desdemona’s misogynistic abuse at her husband’s hands while also holding space and extending sympathy for the racial abuse that Othello experiences. Put differently, the affective, powerful depiction of a white woman as innocent victim can make it difficult to not only attend to Othello’s racial degradation, but also to the ways even Desdemona participates in that process.

How, then, can reanimations effectively respond to the Desdemona problem? As my analysis of Desdemona: A Play About a Handkerchief and Goodnight Desdemona (Good Morning Juliet) reveals, frequently, the impulse is to lean into the Desdemona problem, with creators diminishing or even caricaturing Othello to heighten Desdemona’s plight. Alternatively, the challenge is so hard that reanimations sidestep the issue by excising Desdemona, as do Kill Shakespeare, Othello: The Remix (she is a disembodied voice in both), and even American Moor. The operetta Desdemona, however, offers an alternative approach. In the playtext, Toni Morrison powerfully exposes the misogyny Desdemona experiences within Venetian society, at home with her father Brabantio, and with Othello. Yet by staging confrontations between Desdemona and her servant Emilia, Desdemona and her slave Barbary, who reveals her name is actually Sa’ran, and Desdemona and Othello, Morrison brings to light Desdemona’s classed and racial privilege. In doing so, she reveals that the oppressed can also function as oppressors and suggests that the promise of healing only begins when all parties take accountability for the forms of domination they enact. While no reanimation need exactly mirror Morrison’s tactics, to effectually critique racism and therefore be truly anti-racist, they must account for and effectively respond to the Desdemona problem that troubles so many reanimations of this play.

4. Whose perspective does the reanimation center?

Postcolonial theorist and essayist Ben Okri asserts that in Othello, Shakespeare essentially poured a white man into a Black body.[3] To restate Okri’s assertion, it means that though a Black man technically resides at the heart of the play, Othello nonetheless centers a white perspective because the protagonist is nothing more than a white man’s fantastical creation of Blackness. This centering of whiteness even occurs when Othello gets reanimated much less briefly, such as the short reference to the play in the podcast Serial (Chapter 3). Host Sarah Koenig frames her true-crime investigation of Pakistani American Adnan Sayed’s supposed murder of his Korean girlfriend Hae Min Lee (he has now been exonerated) as an Othello/Desdemona story. I suggest that if Adnan is Othello and Hae is Desdemona, Koenig herself functions as an Iago figure, a narrative orchestrator like Iago who focuses on her perspectives, her affective responses, and her interpretations of each moment over the people of colour on whom she reports. In most versions of Othello, this type of focus on whiteness only directs attention back to figures like Brabantio, Desdemona, and yes, Iago, on almost anyone and everyone but Othello.

Jordan Peele’s film Get Out, however, models alternative possibilities, as I trace in my closing chapter. Get Out’s narrative structure loosely follows Othello’s. Yet while debates still circulate about Othello’s relationship to race, Get Out has been celebrated and widely received as an anti-racist horror film, one that uses music, film angles, plotting, characterization and more to privilege a Black perspective and experience unabashedly. In doing so, the film exposes the horrors of existing in a white supremacist culture without the ambiguity found in Othello. While the details of what centering a Black perspective, Othello’s perspective, will change depending on a reanimation’s given medium, Get Out serves as a vital reminder of how important it is to challenge the perspectival dominance of whiteness in order to make space for new approaches and stories, including new and more racially responsible Shakespearean retellings.

I am not sure which reanimation of Othello will come my way next. Sometimes, I wish the answer were “none,” because despite the anti-racist reanimations I discuss in my book, I am largely skeptical about the need and desire to keep resurrecting this particular play in this day and age. But, if it must be revivified, my hope is that these questions will help us all identify the racial frames that do and do not contest racial inequity in and through Othello so that we can in turn discern which reanimations respond to Othello’s poignant call to “Speak of me as I am” (5.2.352).

Vanessa I. Corredera

Andrews University

Vanessa’s book is available to purchase from Edinburgh University Press. (Use code NEW30 to receive a 30% discount.)

[1] See Ayanna Thompson’s interview “All that Glisters is Not Gold” with NPR’s Code Switch for a discussion of Shakespeare’s toxic plays.

[2] I only recently learned of “colour evasive” as a substitution for “colourblind” thanks to academic twitter. See tweets by professors such as Uju Aynya, Deadric T. Williams, Tina Cheuk, and Darnell Fine that employ the term and suggest it as an effective, non-ableist substitute.

[3] See the essay “Leaping Out of Shakespeare’s Terror: Five Meditations on Othello” in A Way of Being Free (Head of Zeus, 2015).

Header Image: Keith Hamilton Cobb in American Moor.