Eoin Price – The Deep Time of the Early Modern Repertory

23rd November 2022

Eoin Price is Senior Lecturer in English Literature at Swansea University. His current project, Playgoing Time in Elizabethan London is funded by a Leverhulme Research Fellowship.

I am currently working on a project called Playgoing Time in Elizabethan London. The project challenges the dominant tendency of early modern theatre scholarship to privilege a playgoer’s first contact with a play and counters the assumption that playgoers saw plays in the order of their first performance. As part of that work, I am interested in thinking again about what the terms ‘new’ and ‘old’ might mean in the early modern playhouses.

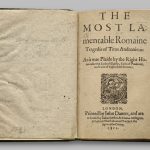

In his financial account book, the theatre entrepreneur Philip Henslowe details daily performances at his Rose playhouse. Henslowe marks some plays with the enigmatic label ‘ne’. Scholars have puzzled over what exactly this marker might mean. Typically, a play seems to have been marked ‘ne’ on its first appearance in Henslowe’s accounts. It is usually assumed, then, that ‘ne’ mostly designates a theatrical premiere. There are, however, exceptions. Shakespeare’s Titus Andronicus is marked as ‘ne’ on January 24, 1594 but, was seemingly performed at an earlier date (it may have received its premiere several years previously). The title page of the play’s print edition, published soon after the performance recorded by Henslowe, unusually associates the play with three different playing companies. How new, then, was Titus Andronicus in 1594? How new was ‘ne’?

What interests me about Henslowe’s administrative marker is that it exposes to view the complexity and contingency of newness as a concept. Titus Andronicus may have been quite an old and well-performed play by the time it received a Rose performance, but this did not necessarily dispel its claims to newness. The play may very well have been new to Henslowe and to many (or at least some) of the playgoers who attended his playhouse. And even if Henslowe and the Rose playgoers had come across the play before that is not to say that the Sussex’s Men performance at the Rose did not seem new in some way or other. Henslowe’s attempt to define newness (and our scholarly dissatisfaction with his idiosyncratic records) tells us something important about the dual concepts of new and old, which were so central to the structure of the early modern repertory and the subsequent scholarship it has inspired.

In Playgoing Time in Elizabethan London, I am interested in challenging the ingrained assumption that a new play is a recent play. Newness is subjective, relational and much more nuanced than our scholarly vocabulary is ordinarily able to acknowledge. Newness is not a stable or straightforward category and the repertory format, which Henslowe’s accounts outline in detail, complicates the idea of the new and its relationship to the old.

Theorists of new media have done much to address the complexity of newness as a concept and this large body of scholarship offers theatre historians new ways of thinking about newness (although I write this sentence with tongue firmly in cheek, for how easily can we speak of new ways of thinking given the contingency of newness?). Consider, for example, Siegfried Zielinski’s work on the ‘deep time’ of media and the wider body of media archaeology work it is a part of. Drawing on geological theories of deep time, Zielinski is inspired by the idea of the earth as a cyclical, self-renewing entity whose history is observable in its sedimented layers. Such a vision of time disrupts chronological, linear and teleological approaches to temporality. The history of media is not a relentless pursuit of technological evolution in which new media supersedes old. Supposedly old media returns, or remains, or is reshaped or renewed. The new sits alongside the old and each informs and reforms the other.

The early modern repertory has its own kind of deep time. Playing companies typically performed a different play each day of the week. Companies periodically premiered new plays, but they continued to perform older ones. Some plays, it seems, dropped out of use completely but often old plays would be returned to use at some point, sometimes in an adapted form. A brand-new play would be performed alongside plays that first premiered weeks, months, years, or decades earlier. Scholars understandably want to get a handle on who performed what and when, but it isn’t clear that playgoers were as bothered by such concerns and the early modern repertory seems deliberately to make it difficult for playgoers to ascertain the age of the plays they watched. Thinking about the early modern repertory in terms of deep time entails us untethering the idea that new and old are concepts that map easily on to chronological, calendar time. If we are to understand what it was that might have made Titus Andronicus seem new in 1594, and if we are to apprehend the complex temporality of the repertory more fully, we must be prepared to let go of some of our foundational assumptions about theatre and time in early modern England.

Eoin Price

Swansea University

Header Image: Title page of the 1594 edition of Titus Andronicus. Folger Shakespeare Library STC 22328.